Classroom Process: Re-imagining Song Lists in the Kodály-Inspired Music Room

Posted on January 1, 2024 in Issue 2: Winter, Kodály Envoy, Volume 50

Larena Code Boyle

Music educators across the country have been rethinking their song lists. As the problematic histories of many American folks songs have become more widely known, teachers have removed them from their repertoire or indefinitely hit pause. What songs do we replace them with? Or should we do more than simply replace? Are there other gaps that need to be filled, in addition to their musical concepts? How can we evolve our song lists and practices in a sustainable way? As an elementary music teacher and clinician presenting on topics related to this, these are the questions I reflect on the most.

I’ve found that due to my Kodály training, I have certain tools at my disposal that can help me tackle these concerns in a way that centers my students, avoids burnout, and steadily fosters a sense of inclusivity and belonging in my classroom. This Kodály-inspired toolbox includes: a philosophy of inquiry, a background in research, skillful folk song analysis, multiple modalities of learning, child-centered sequencing, and joyful collaboration. Each skill can be aligned with a stage in my continuous journey to becoming a more anti-bias and inclusive teacher.

Below are the steps I continue to return to in my journey to diversifying my repertoire and beyond. The stages include: assessing my curriculum, setting aside problematic songs, diversifying my repertoire, creating connections beyond notation, normalizing meaningful conversations, and learning from culture bearers. Personally, I have found that this is a slow-and-steady journey. Every year I try adding another stage or layer, rather than trying everything at once. As a white music teacher especially, my journey is never complete!

A Philosophy of Inquiry: Assessing My Curriculum

As a Kodály-inspired teacher, I am always seeking research-based frameworks to help strengthen my work. Learning for Justice (2017) identified four domains to help educators not only create more equitable environments but also teach the knowledge and skills to their students. The domains are: Justice, Diversity, Identity, and Action. I use these domains to organize my thinking and assess my curriculum and repertoire list. When assessing, I ask myself these questions:

Does my repertoire list work towards disrupting musical stereotypes and uncovering bias? (Justice)

Does it lift up and build empathy toward marginalized musical genres and cultures? (Diversity)

Does it validate and acknowledge my students’ musical & cultural identities? (Identity)

Does it help cast a vision for the future and empower my students to become change-makers? (Action)

A Background in Research: Setting Aside Problematic Songs

I no longer teach songs with problematic or racist pasts like “Skip to My Lou,” “Canoe Song,” or “Shoo Fly,” and continue to research the roots of new songs I learn. Kodály-inspired teachers are trained in searching for and discussing the origins of folk songs. If I am unsure about a song’s past, I indefinitely hit pause on teaching it until I can learn more. Crowd-sourced resources, like Lauren McDougle’s Songs with a Questionable Past (2019), are a wonderful starting point for locating resources that explore these topics.

While some of these songs may be connected to cherished memories or unavoidable in society at large, it’s my duty as a music educator to create an environment at school where no one’s identity is put down. Music has the power to evoke nostalgia and strong emotions, that is exactly why I must think about my students’ future relationship with the music I make and explore with them. I have a responsibility to ensure my students are drawing from a repository of songs that will continue to give them joy, meaning, and inspiration into adulthood. For me, this includes setting aside performance of songs that cause harm for historically and currently marginalized folk.

Skillful Folk Song Analysis: Diversifying Repertoire through Literacy Goals

After setting aside a problematic song, I next determine what musical concept was removed with it. In my Kodály training, I honed my analysis skills enough to feel confident in picking out what child-developmental musical concepts a song has to offer. Finding a new song to replace the missing musical concept provides the opportunity to diversify the repertoire culturally. This also serves as an actionable way to demonstrate to my students that songs from currently or historically marginalized cultures are just as worthy of exploration and musical scrutiny.

At its best, diversifying our repertoire gives students opportunities to learn multiple ways to understand music, themselves, and the world around them. However, when it is done too quickly there is the risk of extreme simplification, teaching in an oppressive nature, or tokenization. When not done at all, it could have the same negative consequences. However, music teachers do not have to become fluent in all cultures in order to foster inclusivity in their curriculums and teaching practices. Below is an activity I created around this stage in my journey that I still use today in my classroom.

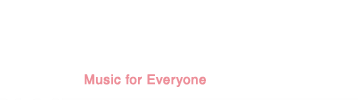

Song Example: “Ache Kuwwa” from First Steps in Global Music by Karen Howard (2020, p. 74)

Howard (2020) shares that “Ache Kuwwa” is a folk song from Pakistan that tells the fable of the crow and the pitcher. This fable is found in many countries and has themes of resilience.

Practice Activity: Ti-Ticka [eighth note – two sixteenths].

I begin this activity by asking my students, “Even if you don’t speak Urdu, I wonder if you can still figure out what this song is about?” After singing the song while showing pictures for each phrase, I guide my students to translate the story using the visuals. I then share with the class that these lyrics are from the fable The Crow and the Pitcher. My students listen again and identify themes of resilience along with prominent Urdu words (crow, pitcher, water, pebbles, rose up). Now that my students have heard the song at least four times, I ask them to raise their hand on the ti-ticka [eighth note – two sixteenths], which occurs in phrase two. We isolate this phrase and the students take ownership. At this point, we sing the song in its entirety: I’m in charge of singing phrases one and three and the students are in charge of phrase two. This approach also helps students have success singing a song in a language they may be unfamiliar with. We pick up learning the rest of the song the next lesson.

Click for a larger image

Multiple Modalities of Learning: Creating Connections beyond Notation

In addition to replacing songs for their musical concept, I then started selecting repertoire based on its connection to a current event, cultural topic, or community theme. Although notation and aural skills are still integral to my curriculum, they are no longer the primary focus of every song or the driving force behind selecting a song. Connecting songs from diverse backgrounds to our existing curriculums helps students see that there is more to the music world than the Western European classical canon.

Kodály-inspired pedagogy highlights multiple entry points of understanding in order to ensure student comprehension. Every song offers inherent musical properties and most present a social history as well. Honoring a song’s original and social-historical contexts helps music educators take another step toward intentional inclusion of diverse traditions. When we learn about the people behind a song, it provides a deeper understanding of that song as a whole. This also serves to validate multiple identities within and outside of our music rooms. Below is an activity that explores notation then goes deeper by connecting to a community theme.

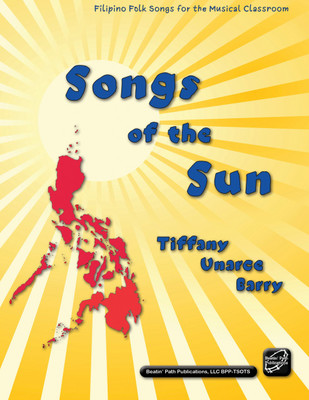

Song Example: “Sasara Ang Bulaklak” from Songs of the Sun by Tiffany Barry (2020, p.28).

“Sasara Ang Bulaklak” is a well known circle game about flowers. Songs of the Sun is a Filipino songbook by Filipina music educator Tiffany Barry. Barry includes personal connections as well as rich cultural context and pedagogical ideas.

Prepare Activity: Re

Students walk in a circle as I sing this song, they must stop on reyna (queen). I then share that this song is about a flower and asks students to count the number of bulaklak (flowers). I sing again as we walk in a circle, remembering to stop on reyna and adding an additional challenge of clapping and singing on bulaklak. This repetition helps students feel comfortable with the song. After we play the circle game a few times, most students are able to sing the whole song. Next, we isolate measure one and identify that the melody is moving upward in steps. Students are guided to identify “ang” as the “new sound” in between do and mi, and we move sampaguita flower visuals to reflect this contour. The sampaguita flower is the national flower of the Philippines. I then share that these flowers often symbolize strength and change, which must start with planting and nurturing a seed. As a class, we discuss what “seeds of change” we would like to plant in our community.

Child-Centered Sequencing: Normalizing Meaningful Conversations

Sharing a fuller context of each folk song sparked so many connections with my students and helped them feel empowered to share their own experiences. This encouraged me to engage my students in further conversations about the world and their place in it, in order to experience the full extent of my diverse repertoire list. A song from another culture does not need to be treated as a museum piece, frozen in time. In addition, using our “tried-and-true” American folk songs as fodder for deeper topics is a way to introduce multi-faceted representation. This helps students treat songs more equitably.

The Kodály approach emphasizes the importance of teaching in such a way that is natural to the child. Through scaffolded questioning, the teacher guides students from what they know to what they have yet to discover, in a developmentally-appropriate way. I started using this skill to frame discussions around identity, race, or other complex topics in a musical context. Providing consistent opportunities for our students to take action can help them feel less anxious about issues that may personally affect them. Below is an activity I use that exemplifies crafting questions that guide meaningful conversations in a musical environment – while still centering play.

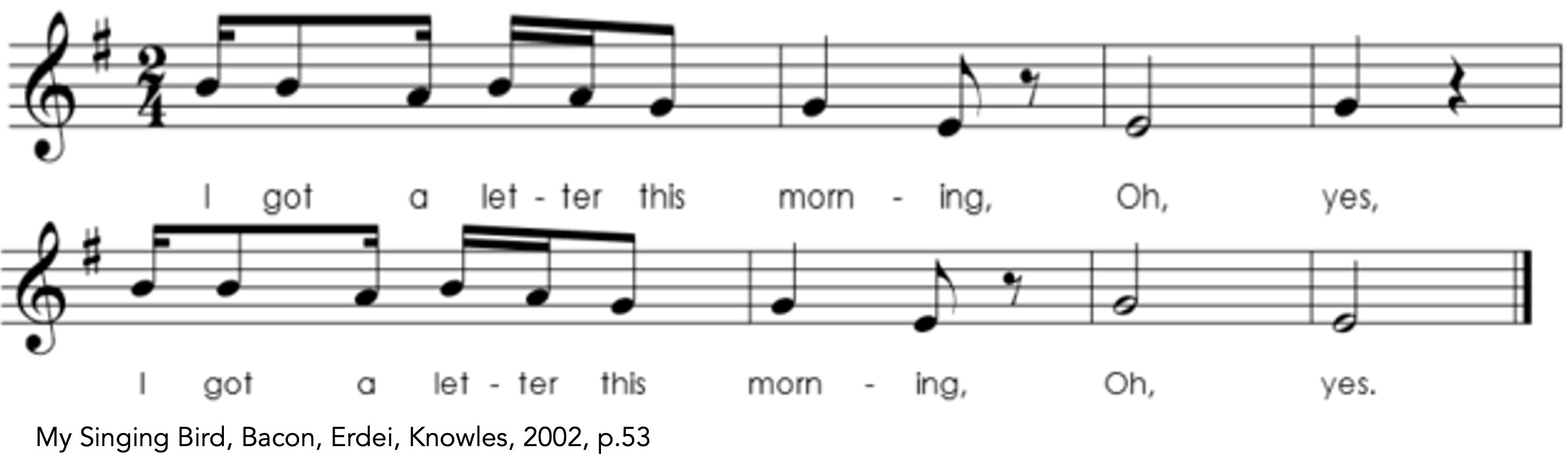

Song Example: I Got A Letter (U.S.) from My Singing Bird by Bacon, Erdei, Knowles (2002) p.53 and Brown Skin Girl by Beyoncé (2019)

Prepare Activity: Low La

After playing the hide-and-seek game, students aurally identify both “oh yes” motives using staff visuals that I’ve hidden inside the envelopes. I share with the students that “Oh yes” is a way to affirm what someone has said. As a class we define affirmations and share there are many in the story I Am Every Good Thing by Derrick Barnes. I read the book and as a class we sing “Oh, yes” every few pages. I remind students to watch for my hand signs so they know which motive to sing (la, – do or do – la,). After the book, students are encouraged to speak their own affirmations using “I am..” or “I love my…” The class listens then sings the “Oh yes” response. Next class, we listen to Brown Skin Girl by Beyoncé to dig deeper into affirmations and the importance of Black and Brown children hearing their skin color being affirmed joyfully. Together we reflect on why Beyoncé might have written the song.

Brown Skin Girl by Beyoncé

Joyful Collaboration: Learning from our community and culture bearers

In addition to normalizing conversations with my students, I found that sharing and learning regularly from my community was just as useful. Music does not stay in the music room and we cannot do this work alone. When we invite culture bearers (be that recordings or in-person experiences) into our music rooms, this adds another dimension to our songs and informs a more nuanced and multifaceted approach.

It is easy for our students to perceive their music teacher as the sole knowledge-giver of music, but it is important to de-center ourselves. Collaboration promotes collective musical wisdom and reminds students that no one is a monolith. We can seek collaboration with our students, guest presenters, our non-music colleagues, and each other!

Reflection

Which step do you resonate with? There is no single perfect way to engage in this work: start where and with as much as you feel comfortable. I fluctuate between all of these stages, making sure to strengthen one when I fall behind on it. Our journey never ends. Elementary music teachers get the joy of providing a rich foundation of musical and social learning for our youngest learners. We have the opportunity to support healthy identity formation, amplify ownership of our students’ ideas and voices, and build a respect for other people, races, and cultures. It is my hope that you were affirmed in some of your current practices and inspired to create new approaches as well. This is joyful work! As Dr. Cindy Acker proclaimed, we must continue to search for and teach songs that “speak resistance, speak peace, and speak justice” (Acker, 2022).

Biography

Larena Code Boyle is a full-time elementary music teacher at the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools. She frequently presents workshops at the local and national level on topics such as inclusive repertoire, Kodály-inspired teaching, and culturally relevant curriculum. Larena holds a Master’s and Bachelor’s in Music Education and is fully certified in both the Kodály and Orff Schulwerk approaches. She won the Outstanding Emerging Educator award in 2022 through the Organization of American Kodály Educators. For more info visit larenacode.com.

Works Cited

Acker, C. (2022). Holding the tension of the two opposites remaining true to Kodály’s vision. [Keynote address]. Midwest Kodály Music Educators Association 2022 Conference.

Barry, T.U. (2020). Songs of the sun: Filipino folk songs for the musical classroom. Beatin’ Path Publications.

Beyoncé, Saint Jhn, Wizkid, feat. Blue Ivy Carter. (2020). The Lion King: The Gift [Album] Parkwood, Columbia.

Black Banjo Songsters. (1998). Black Banjo Songsters of North Carolina and Virginia [Album]. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Eisen, A. & Robertson, L. (2010). An american methodology: An inclusive approach to musical literacy (2nd ed). Sneaky Snake Publications.

Learning for Justice. (2017, June 28). Social Justice Standards. Retrieved November 12, 2021 from https://www.learningforjustice.org/frameworks/social-justice-standards

McDougle, L. (2019). Songs with a questionable past. Retrieved Nov, 13, 2021 from https://docs.google.com/document/u/0/d/1q1jVGqOgKxfiUZ8N3oz0warXefGIJill2Xha-X5nUY/mobilebasic?fbclid=IwAR3M9f-29AMhLZjoQ4qudoOyLXQ5Kwfu_fhdrjDPg7HMSPw2BtJQIQ5zRGY

Howard, K. (2020). First steps in global music. GIA Publications.

|

Share this article to Facebook |

We hope you’ve enjoyed reading this public article from the Kodály Envoy. Interested in reading more?

OAKE Members get access to the entire Envoy archive; 50+ years of Kodály-focused articles and research.